Warped Solace

Julia Egbert

Mid-fire red stoneware from Greece; overfired

During my time in Greece I had the opportunity to make things there out of Greek clay. I threw a bowl and burnished it, and I hand-built two halves of a sea urchin as well as a butterfly on a flower, meant to be an incense holder. It was arduous and time-consuming making them, but I found joy and respite from the stresses of life in a foreign country while making them These objects could not be fired in Greece, so they had to travel with me back to Michigan.They were packed in a carry on bag with towels, thrown in the belly of a plane for an 11 hour flight, shuffled off and into an Uber for a stay at an infamously sketchy hotel in Toronto, shoved in the bottom of a bus for a 6 hour drive across the border, and finally a 2 hour drive back to East Lansing. Miraculously, they survived the trip mostly unscathed.

Then upon arrival at MSU, they were bisqued, glazed and fired to cone 6 only to become what you see now. Yet they were strangely beautiful as a melted conjunction of all my experiences of Greece and the adventure of being abroad in general.

The Wide Stones Scare Me

Nahom Ghebredngl

Wire, wood, paper, plaster, acrylic, slab-built press-molded mid-fire stoneware

I stand on the wide stone steps of the Sacred Way and look up to see what was once the temple of Apollo. Resting on a steep incline near the peak of Mt. Parnassus, this was once an ancient place of worship, divining, social gathering, and political maneuvering. Set into the cliffside are thousands of years of human history and generations of people before my time.

Looking away, I peer into a deep valley filled with cypress trees, winding rivers and small country roads. Further still and out of sight is the Gulf of Corinth.

Greece is filled with places like this, with ancient ruins set square between rugged mountains and a clear blue sea. Amidst these things, among the signs of a deep human history and breathtaking landscapes, I can’t help but feel small, brittle, and fleeting. All at once the world opens and I feel part of a cosmos too large for comprehension—I must find shelter from this feeling and build a purpose that, in the face of this barely intelligible vastness, won’t infuriate me the with its idleness.

From this fear, I found shelter with my family and friends, and after that I looked for stillness and meaning in this work. This is how I choose to carve out my place in the cliffside. How I demand life from wide death. By searching in the curves and bumps. In the colors and textures.

I hope to keep searching, until my time here is up.

Sacred Spaces

Christi Lopez

Press molded, wheel finished, mid-fire stoneware

Greece has sacred spaces in abundance. Everywhere you look, you can find evidence of the rich culture and deep roots of a history celebrated the world over. But what makes a space sacred?

Personally, it’s not about what people have done to the land. Certainly, the ruins of ancient temples and artifacts that reach through time all indicate a sacred space. But it is the connection I feel to a space that makes it sacred. In Greece I found my sacred spaces in quiet moments…watching the sunrise while floating in the Aegean Sea, feeling the wind against my skin as I climbed Acrocorinth, feeling the stones beneath my feet as I walked the paths at Delphi. These moments all touched my soul.

For me, working with clay offers a similar sacred experience. There is something about shifting and molding the medium that is therapeutic. To watch clay pieces transform through firing and then again through glazing, all without complete control over the outcomes is freeing.

The pieces displayed here meld the feeling of my sacred spaces in Greece with the sacred experience of working with the clay. Both brought me peace and calm, and I hope they bring the same to you.

Trench 23

Morgan Manuszak

Mold made, hand finished, mid-fire stoneware, acrylic paint

As someone studying archaeology, being involved in the manufacture of ceramics has been an eye-opening experience. The things I’ve been taught about how to analyze ceramics flew out the window once I began working with clay myself. It was like the world went from black and white to technicolor.

This body of work is simultaneously a reflection on my personal experiences in Greece as well as a consideration of the archaeological collections of lamps that we see within the field. Throughout antiquity, the shape and decoration of oil lamps changed frequently, and as such they are key indicators of time periods as we uncover them. But as offerings and ritual objects in the ancient world, they also functioned as artistically crafted symbols of great meaning to their dedicants.

The lamps I’ve created represent similar, yet much more personal, changes that took place over the course of my time in Greece. I see myself in each of these lamps, especially as I explore the notion of what it means to sacrifice one’s time or energy for the greater good of a collective. The vessels themselves explore the traditional means of carrying and preserving light, and what that means when transposed onto a personal subject. By utilizing traditional motifs and techniques, I hope to capture my connection to the past while simultaneously reflecting on how I maintained my inner flame during this trip.

A Necessary Evil

Ally Miscikoski

Hand-built low-fire white earthenware

While in Greece, I took particular interest in its ancient representations of women in art and mythology. From the Amazons and Theseus, the origins of Athena, Hades and Persephone, the list goes on. But it was the mythos of gorgons that spoke to me the loudest.

First, there is the story of Medusa: Raped by Poseidon, blamed, and made monstrous as punishment by the goddess Athena, she was later beheaded by the “heroic” Perseus. Yet this brutal, and oddly normalized myth is not the only story. There is a Greek myth that states blood taken from the right side of a gorgon could revive the dead, while blood from the left side is an instantly fatal poison. And, in ancient Greek architecture, Gorgoneions were decorative motifs used to protect against evil forces. Yet, Gorgons themselves are portrayed as evil by nature. This contradiction strikes me as reflective of society’s view of women throughout history as a necessary evil. To paraphrase the Greek writer Hesoid, “the only thing worse than a woman is not having a son.”

We expect women to be pure, to take care of our homes, to raise our children, and to be a source and object of love. However, they are often portrayed as unpredictable, conniving, gossiping, easily corruptible, alien, and selfish. They are incapable and undeserving of independence. It is a strange and cruel balancing act between the representation and expectation of half of all humanity, and trying to conceptualize this idea as a woman has been quite eye-opening.

I wanted to sculpt an image of those polarizing ideas of what women should be and what women are through that twisted lens of history: necessary to carry on the family name, tolerable if controlled and obedient, and evil otherwise.

Shifting, Pulling, Changing

Marissa Rubaiai

Slab-built tiles, oil paint, wood

During the last year of my life I felt disconnected with myself due to wounds caused by close relations. I used the trip to Greece as a way to rebuild myself back up and let go of the pain being carried. Not only was I inspired by nature, artifacts, and history, but the artist Panos Valsamakis that we visited stuck out most. His tile works were like puzzle pieces that fit together uniformly. Which in contrast made me think back to many things from the ancient world, and how they are broken, and reassembled from old, shattered pieces. I combined these 2 inspirations to speak on the healing journey I was undergoing. Using an organic shape unlike Panos’s tiles, allowed me to frame the person into an isolated shape that restricts and focuses the movement. The tiles are symbols of breaking internally, and out of a time I was stuck in. They are sturdy alone, but have more strength when pieced together. These pieces are being forced to work as a layer of skin that’s breaking. I believe humans are assembled into pieces that shift as we change. Previously, it felt like I needed to rip off my skin in order to heal into someone new. In reality, we can just shift our pieces, add new ones, let go of old, heavy ones, and rebuild in a way that fits better. This process is extremely painful and isolating. A feeling I endured during my time in Greece.

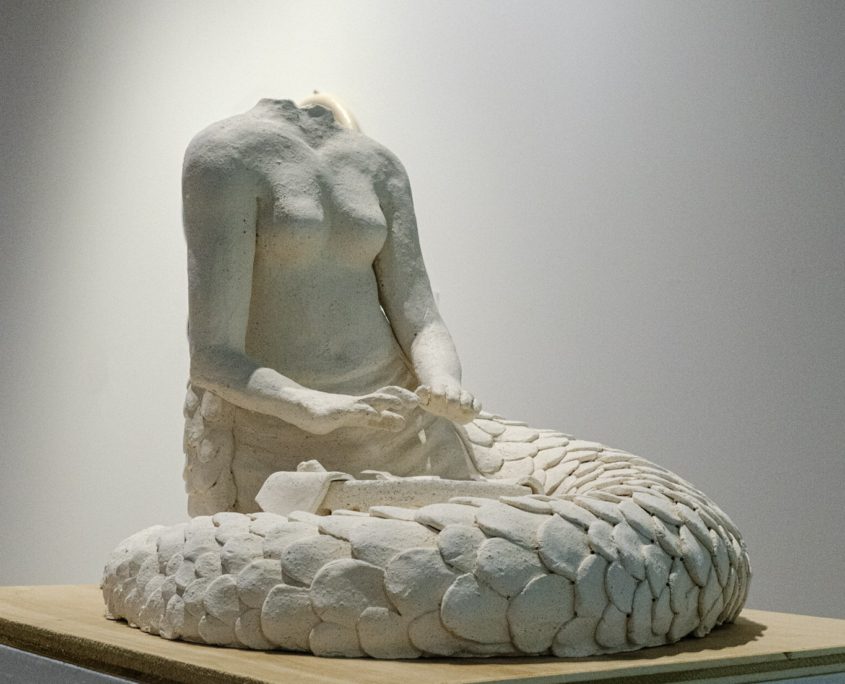

Mythology of the Self

Mackenzie Sheehan-D’arrigo

Low-fire red earthenware paper clay, metal, acrylic

It fascinates me that objects handled and worked by hands over 5000 years ago exist to this day. In a place with history as rich as Greece, and in holding ceramics millennia old with my own hands, it is easy to feel lost in the grandeur of it all. Still, I am equally intrigued by what is no longer there, and what is soon to disappear. I find myself attracted to the most minute details— the textures, surface treatments, and inscriptions of archaeological works from temple walls to terracotta vases. The use of paper clay allows me to memorialize this aging process, because while they provide extra strength in building as they intertwine amongst themselves, the fibers leave the fired clay extremely fragile after the paper burns out. This piece features delicately attached coils pressed into patterns inspired by crumbling castle walls, imagined silhouettes of ancient Greek architecture, and what lies below the surface. In constructing the intricately patterned walls, I reminisce on my time navigating territory unknown to me, which oftentimes includes my own self. Archaeologists, too, face the idea that there will always be unknowns, and that time will erode what once flourished, but it doesn’t stop them from reconstructing and reframing with each new piece of knowledge gained.

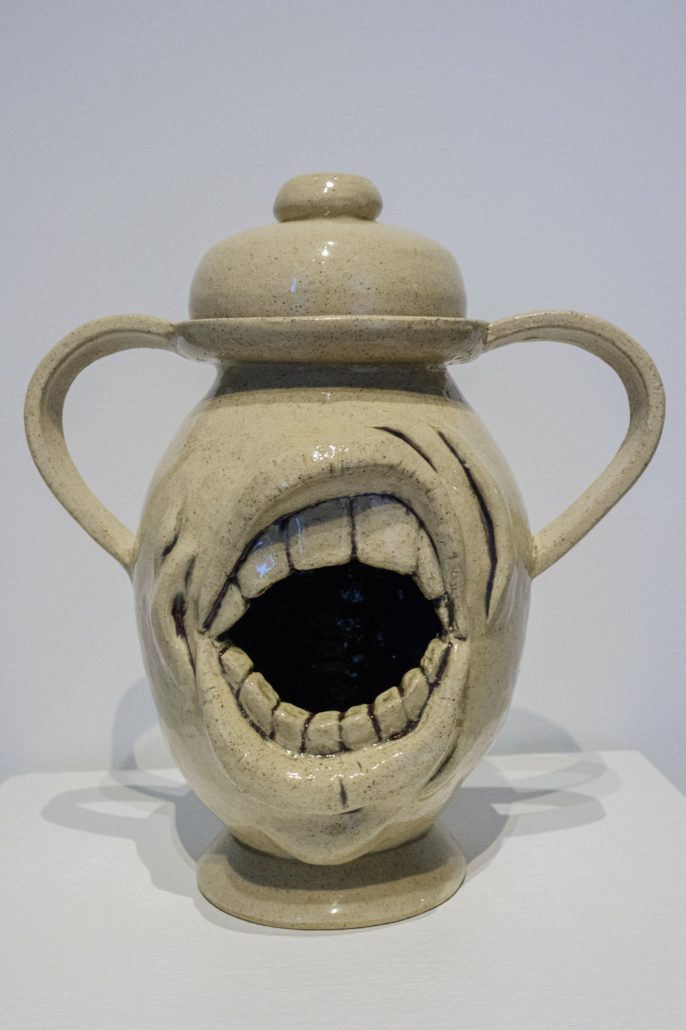

Open Up

Liz Vadella

Wheel-thrown, altered mid-fire stoneware vessel

I have struggled to fit in with others my entire life. Learning social cues doesn’t

come naturally to me and being in a group setting adds complexities to interaction.

There are too many details to consider, so I find myself staying quiet, too afraid of saying the wrong thing. In the first half of my trip to Greece, I felt myself disappearing. It is not easy when the people around me seem to get along so well and when everything I say seems to come out wrong. I have so much to share with others, but I scare myself into silence until I become someone that I wouldn’t even want to be around. At a certain point, I began to wonder if I even knew who I was. It made me want to yell.

But then, one day I was sitting at the shore of the Aegean Sea with my head in my hands when someone in the group truly saw me for the first time. In an overwhelming situation, she was there to ask how I was and give me a space to be myself. I didn’t even know how much I needed that.

I want to have meaningful, authentic relationships. I want people to trust me

enough to be themselves when they are with me, but I realized on this trip that it

starts with me. To connect with others, we first need to open up.

Terminus Post Quem

Megan Weaver

Plexiglass, sand, wood, stone, wood ash, hand-built and wheel thrown mid-fire stoneware mementos

This work combines three moments of inspiration.

First, throughout my time in Greece, I was drawn to the offerings made to the goddess Demeter. Each museum we visited had a plethora of tiny animals, vases, women, and food made from clay, wood and stone. I often thought, how were these objects related to this goddess? Maybe they were significant to her life, but the diversity of the objects suggested that they held even deeper meaning in the lives of her followers. Thus at the studio, I found that I too wanted to create objects that were important to my life’s story. Each miniature represents a different memory, some traumatic, some nostalgic, but all significant to my story.

Second, I became interested in the way that things become buried, even in a busy city like Athens. There, we came across a Byzantine era church that sat on a plot of land several feet below contemporary ground level. While the church remained still, the city continued to grow up around it. At archaeological sites these layers become even more apparent, each a distinct era. In my piece, each sand type represents a different period of my life. Sand preserves objects while also making them invisible. Just like childhood memories, the objects are still accessible if you just dig deep enough.

Third I noticed that along the roadsides in Greece there are these beautiful mailbox sized structures shaped like churches. Often marking places of loss or miraculous salvation, these structures are the Greek equivalent to roadside crosses. They often have sides of clear glass and a door on the front. Inside these boxes are images of saints, offerings, and candles. They house and protect something precious in remembrance of someone. They became the inspiration for my container. My box was created in remembrance of my past selves and the memories they created. Past selves that I will never be again. With each layer of sand, I let go of these eras of my life.

We thank the following individuals and programs for their support of this study abroad experience and the resulting exhibition.

MSU College of Arts and Letters

Department of Art, Art History and Design

MSU Excavations at Isthmia

Ceramics Center / Manolis Drilierakis

Global Arts Studio / Sokrates Lambropoulos

Jasper Ceramics

Mirella Studios / Anastasia Petikidis

Mon Coin Studio / Eleonore Trenado

Pink Dolphin Studios / Rania Totsika

Pylos Studio / Aris Sichlimiris

Valsamakis Ceramics / Panos Valsamakis

Ioanna Damanaki

Tani Hartmann

Ulrike Krotscheck

Giannis Mamoutzis

Sarah McLean

Allison Miller

Elpida Ntriva

Walt Peebles

Angeliki Stamataki

Jacquelynn Sullivan Gould

Anthi Theodorou

Daniel Trego

Ioulia Tzonou