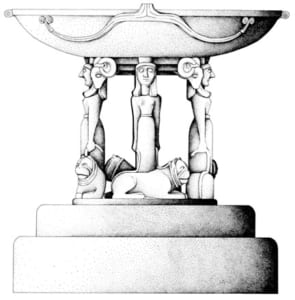

Marble sculpture from Isthmia known as “The Two Cybeles”

As might be expected at any ancient site with centuries of use in antiquity, Isthmia appears frequently in the written sources available to us in Greek and Latin. Many of these accounts inform us about significant events that took place in this busy part of the Corinthia. After all, the central location of the site at a major crossroads of land and sea made Isthmia an ideal location for Greeks to come together to discuss matters of shared concern. But some of these accounts refer back to events that were thought to have taken place in the earliest days, when gods and mortals still inhabited the same spaces.

Myths

Sinis

One myth connected to Isthmia involves the hero Theseus. Having grown to maturity and having learned that he was the son of King Aegeus of Athens, Theseus set out from his native Troezen to claim his birthright. As he traveled along the coast of the Saronic Gulf, Theseus defeated several bandits and other unruly individuals. At Isthmia, he encountered a man who enjoyed a rather peculiar form of entertainment. This was Sinis, also known as Pityocamptes or the “Pine Bender.” According to the stories recorded in Apollodorus, Plutarch, Ovid and Pausanias, Sinis would overpower unsuspecting travelers, then tie them to trees that he had bent downward. Releasing the two trees produced a predictably destructive result, as Sinis himself discovered when Theseus forced him to endure his own torture as punishment.

Theseus defeating Sinis

Palaimon / Melicertes

Palaimon/Melicertes and Sisyphus

By far, the most famous myth associated with Isthmia concerns the local hero Palaimon / Melicertes. According to accounts in ancient authors such as Ovid, Nonnnus and Pausanias, the young boy hero was the victim of Hera’s rage because his parents, Athamas and Ino, had given protection to the young god Dionysus, daughter of Semele and nephew to Ino. Driven to madness by Hera, Athamas attempted to kill his family and in an effort to escape, Ino jumped from the nearby cliffs while holding her son. Moved by sorrow at the tragedy, sea goddesses known as Nereids transformed both mother and child. Ino became Leucothea, the White Goddess known to us from Homer’s Odyssey, while Melicertes became Palaemon.

According to the myth, Palaemon was carried on the back of a dolphin to a place on the eastern Isthmus called Schoinus. There the boy’s body was found by King Sisyphus of Corinth. Far more commonly known today for his eternal punishment in the afterlife, Sisyphus was also brother to Athamas. He ordered his nephew’s body to be taken to Corinth and on the orders of the Nereids, established the Isthmian Games in his honor.

History

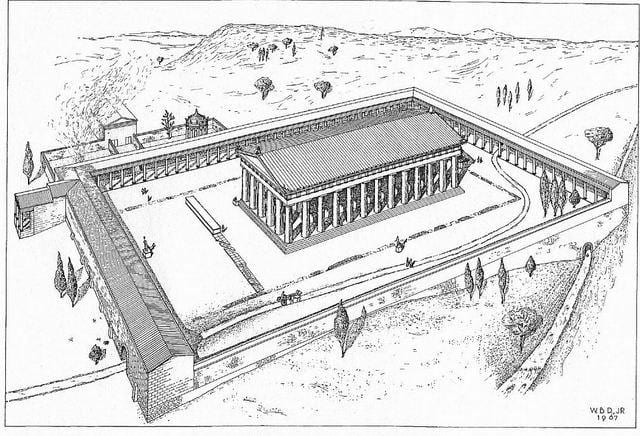

A large Doric temple to Poseidon was built at Isthmia around 700 BC. The site at the Isthmus was a natural spot for the structure, since many travelers passed through on land and there were many ports nearby that served maritime traders. Both the temple and Isthmia prospered because of the Isthmian Games. Around 480 BC the Archaic temple was destroyed by fire. A new, larger temple was constructed about 465 BC, and the games continued. Throughout the next decades there were several conflicts in Greece but the games were held uninterruptedly. However, in 390 BC the games were disrupted when a Spartan army marched on the Isthmus. The temple was damaged again by fire, and because of economic trouble in Corinth, the damage took some time to repair.

Throughout most of the third century the Macedonian kings used Corinth as one of their most strategic garrisons. The Macedonians lost control over Corinth in 243 BC to the Achaian League, but regained it in 228 BC. In 225-4 BC the Macedonians brought an army through the Isthmus to face another Achaian force trying to take Corinth. Since the Isthmus was the crossroads of Greece, armies would continue to march through it, often with disastrous consequences to Isthmia and the Temple.

Archaic Temple of Poseidon

Roman Period Temple of Poseidon

Rome arrived in 200 BC to liberate Greece from Macedonian control; one of the garrisons they took was Corinth. The war against the Macedonians concluded in 196 BC with a complete Roman victory. Before withdrawing his troops the Roman General Titus Quinctius Flamininus chose to make a political statement and a demonstration of Roman goodwill: he announced the complete liberation of Greece. It should come as no surprise that the place he chose to make this announcement was the Isthmian games. By now Isthmia had had a long history as a symbol of Greek freedom, Greek unity, and Greek resistance to outsiders.

Fifty years later the Romans were less magnanimous to Greece. After declaring war on the Achaian League, the General Lucius Mummius (soon to be Achaicus) decided to make another political statement in Corinth. In 146 BC Mummius ordered Corinth to be destroyed and Isthmia shared the city’s fate. The Altar of Poseidon was destroyed, and the Isthmian Games were transferred to the control of Corinth’s neighbor Sicyon. The games probably moved there too. Corinth was later refounded as a Roman Colony by Gaius Julius Caesar in 44BC, and the city-state regained control of the games about forty years later. However, archeological evidence suggests that the games did not return to Isthmia until about 50 AD. At that time, the temple and the facilities for the games were repaired, and in 67 AD the Emperor Nero took part in the Panhellenic Games.

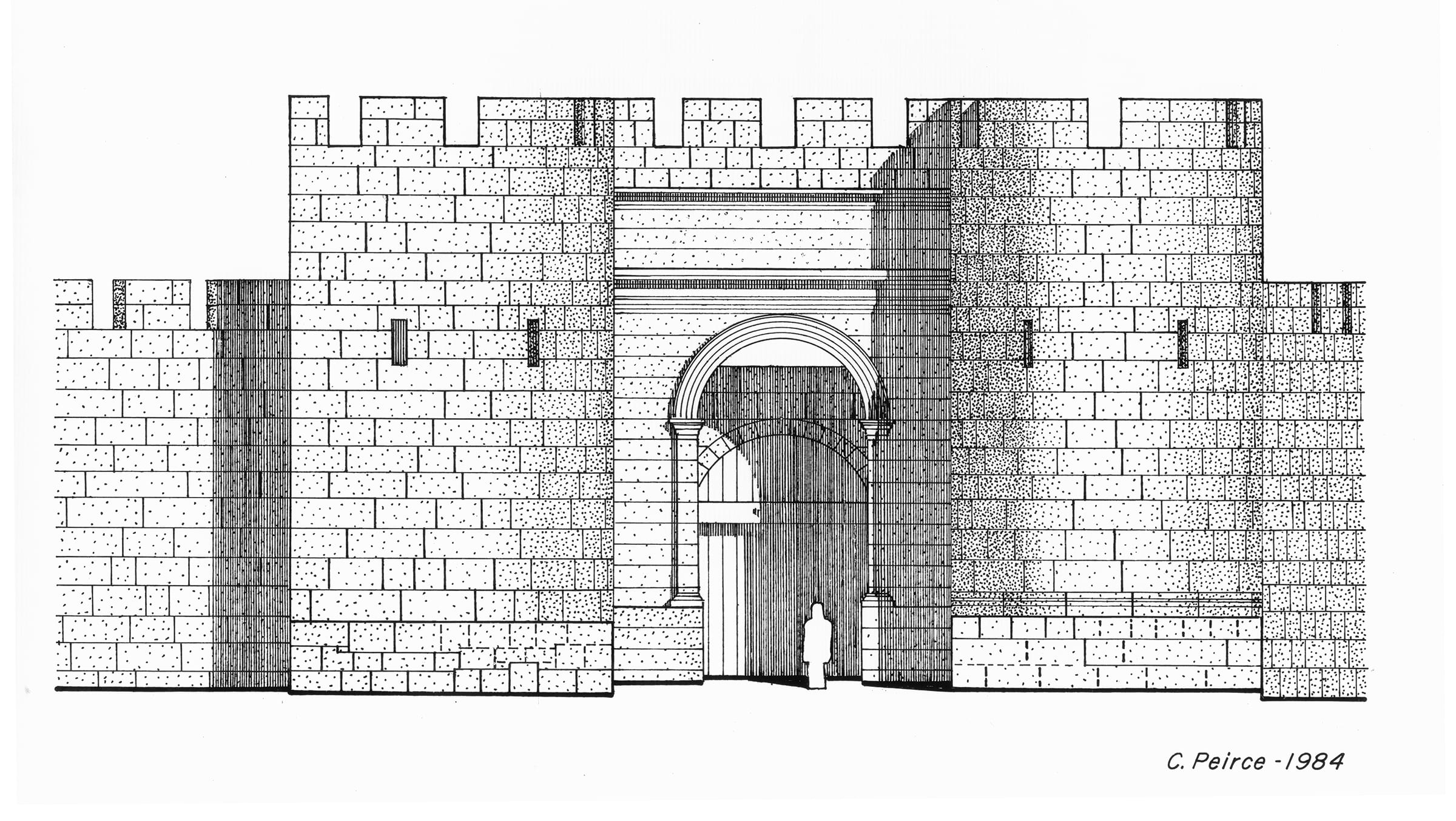

By the end of the 4th century AD Christianity would be the only legal religion in the Empire, and it is almost certain that no more games were given in honor of Poseidon. By 400 AD the sanctuary to Poseidon was an abandoned relic to a bygone era. In the reign of Theodosius II (r. 402-450 AD) a wall was constructed across the Isthmus. The Hexamilion (six-mile) wall required an enormous quantity of stone to construct, and many abandoned buildings were plundered for stone. The temple was torn down to its foundations. Isthmia itself may have been sporadically abandoned between the late 7th century and the 11th or 12th century AD. However, the Isthmus continued to be an important strategic location during the Late Medieval and Early Modern periods.

Northeast Gate into Hexamilion Fortress