Gallery by Daniel Trego

While familiar to many, the expression “classical art and archaeology” masks a problem of identity for those who study the material evidence for the Greek and Roman past. For much of its early history, the work of classical archaeologists was shaped more by an interest in acquiring works of art than in understanding the people and places responsible for their creation. Yet, by the middle of the 20th century, this long standing obsession with the sublime beauty of Mediterranean art began to draw sharp criticism from scholars who wished to reshape classical archaeology into a more scientifically rigorous study of the human past. As a result, fieldwork came to be carried out with an air of emotionless reserve that is thought to typify the “hard sciences.” To be sure, the adoption of scientific methods has done much to improve the practice of archaeology. But it is also difficult to deny completely the aesthetic appeal of these objects of study.

In 2020, thanks to the support of the Department of Art, Art History and Design and the College of Arts and Letters, Michigan State University became the institutional sponsor of the Excavations at Isthmia, an archaeological project in Greece begun in 1952. In 2021, the MSU project hosted its first season of active fieldwork, which was extensively recorded by Daniel Trego, Educational Media Design Specialist at the College of Arts and Letters. The resulting body of work occupies a unique space between archaeological documentation and the creative exploration of objects and practices that are by their nature visually compelling. As a whole, this exhibition captures the excitement and beauty that is archaeological research and asks the question: Can the archaeology of art also be the art of archaeology?

IPR 67-23

Enough of the body of this amphora (a type of storage and transport jar) was excavated to allow it to be partly reconstructed. This image of the pitted and patched interior and exterior surfaces of the pot encourages contemplation of the beauty of this ubiquitous and quotidian artifact.

US21-01

One of the joys of work at Isthmia is the opportunity it provides for information to be shared between generations of archaeologists.

US 21-02

This “pottery pile” consists almost entirely of transport amphorae which served as the shipping containers of the Greek and Roman world. Generally unremarkable in their particular details, these artifacts collectively present an interesting testament to the interconnectedness of the ancient Mediterranean.

US 21-03

In this collision of ancient and modern, a smart phone is used to illuminate the interior of a Roman era cooking pot in a search for the object’s catalogue number which will help with its identification.

US 21-04

This building, acquired by the UCLA Excavations at Isthmia in the late 1960s and now under the care of MSU, is the first thing seen by visitors to the excavation archives.

US 21-07

As this “hands-on” image shows, part of the benefit of summer study at Isthmia is the opportunity to interact directly with antiquities that are more commonly kept behind glass in museums.

US 21-06

While many aspects of archaeological practice and theory can be learned in the classroom, some concepts and techniques are still best taught “in the field.”

US 21-14

The moment captured here as this mended pot receives the attention of a conservator invites questions about the impermanence of our lives in the context of the things we leave behind.

US 21-08

Over the centuries, organic materials like cloth, paper and wood decay and disappear completely from the archaeological record, leaving only the stone and clay behind. In this image, what had been lost is now regained, but only as younger containers for the much older artifacts.

US 21-09

This scene from within the “excavation house” captures well just one of the countless learning experiences that take place each summer at Isthmia. Balancing order and chaos is always a challenge and opportunity in archaeology.

US 21-13

The nearby site of Corinth, which held the honor of overseeing activity at Isthmia, flourished in both the Greek and Roman periods. It is all but certain that this same scene has occurred thousands of times as groups of travelers to and from Isthmia passed through the region over the last two and a half millennia.

US 21-05

Many monuments at Isthmia have been reduced to rubble and foundations, but with careful study they can still be reconstructed virtually. In this image, which hints at a type of religious ritual, students gather images that will be used to build a model of this temple podium.

IS 71-2 and IS 71-3

These two small marble busts were discovered on the same day in one of the richest deposits of sculpture ever found at Isthmia. The arrangement captured here encourages contemplation of possible conversations had over centuries of shared sequestration.

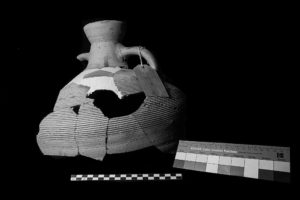

IPR 77-18

The paper tag that hangs from the handle of this partly reconstructed amphora (a type of storage and transport jar) evokes thoughts of luggage tags, which, oddly but appropriately, recall the vast distances that this type of vessel once traveled.

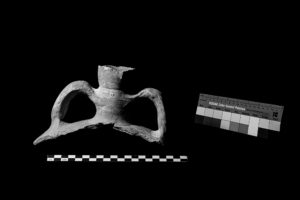

IPG 68-164 a/b

This oiochoe or ‘wine jar’ was manufactured in nearby Corinth in the early 6th century BC and discovered in a cemetery just west of the sanctuary at Isthmia. That it was not found in a grave suggests it may have been part of a commemorative feast.

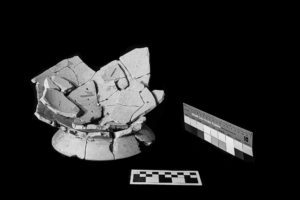

US 21- 12

Sometimes there just isn’t enough left of an ancient pot to justify a restoration. In these cases, pieces of vessels are placed in boxes in the hope that future excavations will yield enough to complete the shape.

IPR 90-2

This is part of an amphora, which was a large jar originally used to transport goods across the Mediterranean in the Roman period. The fact that it was found in the construction debris of a building suggests that it may have served a second function carrying building supplies or as simple fill.

IP 3856

Because archaeology is equal parts luck and preparation, sometimes missing pieces are found after the pots to which they belong have been mended. This two-handled cup reveals an interesting use of tape keep the pieces together until the vessel can be properly mended.

US 21-16

It is common practice in archaeology to mark objects with catalogue numbers that can be used to connect them to the records of their discovery. In this unique example, the number was adapted from the volume and page number of a field diary.

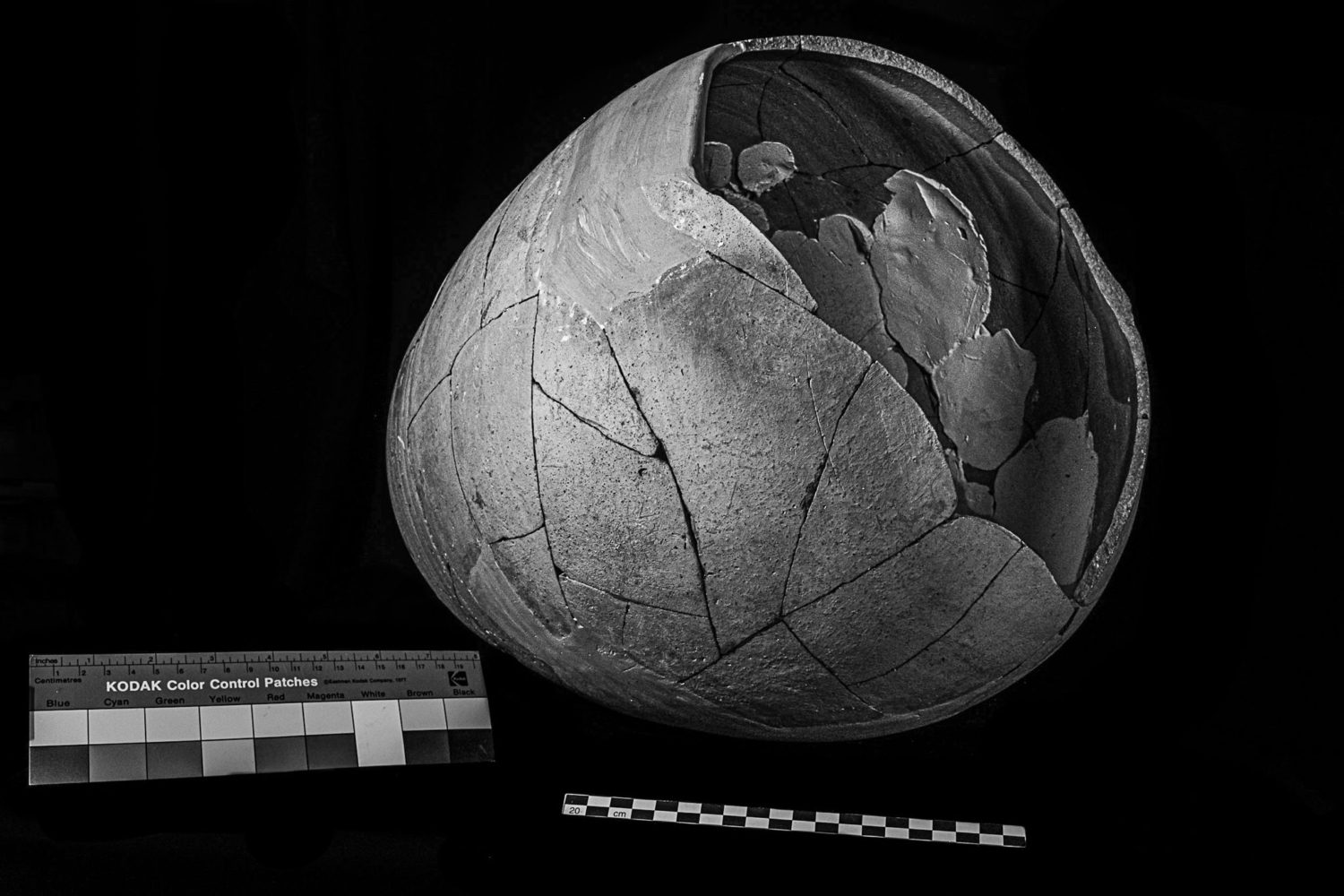

IPG 68-262

This krater or ‘mixing bowl’ was created in nearby Corinth, most likely in the 6th century BC. This image captures an interesting irony—the pairs of holes drilled through the thickness of the pot are the remnants of an ancient repair, but sadly not enough of those pieces remain to attempt to fix it a second time.

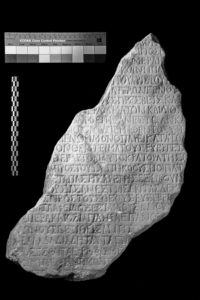

ΙΣ 70-2

One of the longest inscriptions found at Isthmia, this fragmentary decree describes honors given to a high priest who repaired religious buildings at the sanctuary. There is a certain irony in the fact that this object was itself used as building material in a later wall at the site.

US 21-10

As a repository for thousands of ancient artifacts, the MSU Isthmia “excavation house” commonly receives requests for images for study and publication. Oftentimes, it is easier to set up an impromptu photography station than to move a collection of pottery to a studio.

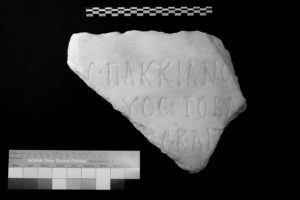

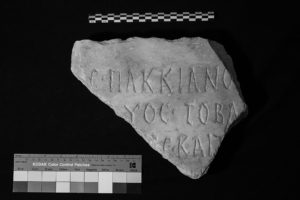

ΙΣ 70-6 and ΙΣ 510

These two fragmentary inscriptions, one of which clearly features the name of Pakkianos, a 2nd century AD official at the Isthmian Games, serves as a good example of how much our perception of archaeological evidence depends on the skill and artistry of the photographer.